Nike Dunks and The Evolution of Street Style

- Reginald Ferguson

- Oct 31, 2023

- 18 min read

Updated: Jul 29, 2024

Want to dive into the world of Nike Dunks, see how Virgil Abloh shook things

up, and get the lowdown on the Bronx's role in streetwear history? Read on.

I’ve been hearing and seeing so much about Nike Dunks lately. From the late Virgil Abloh and his iconic reimaging of the style, to having a guest on my podcast talk about them as his favorite sneaker (and the silhouette he used to create his own sneaker) to seeing them being sold on GOAT at exorbitant prices.

An image of the Off-White Nike Dunk Low in Pine Green colorway.

When I read about “streetwear” in this context, I’ve noticed there never seems to be a link between the present and the past, as if the genre created itself.

Most important is the ignoring of its roots in Hip Hop culture which is where “streetwear” came from and the debt it is owed.

Unearthing the Roots of Streetwear and Athleisure Streetwear and athleisure weren’t born from Hypebeast or Instagram.

They descended directly from an urban youth movement created by Blacks and Latinos in New York City that grew in influence and popularity, decade through decade, right up to this day. Why acknowledging Hip Hop's influence in fashion matters If you love wearing those styles today, especially sneakers and tracksuits, then you are the

direct descendants and beneficiaries of an earlier generation of influence.

Why is this important?

Because this culture was built from scratch by African Americans and Latinos, and too often the contributions of these groups are ignored once they are subsumed by the greater American popular culture.

Because Hip Hop opened up the contemporary era to strong colors, bold graphics and logos and a more casual and acceptable look with influences from prep, skate culture and punk.

Because the Hip Hop era created some of the most enduring fashion phenomenons like

“sneaker culture” and tracksuits.

To ignore its current influence and the contributions of people of color would be to ignore history.

In light of the most recent racial pandemic that has been recorded, consumed and shared by the masses it is more important than ever to acknowledge these contributions. My Personal Connection to the Birth of Streetwear

Hip Hop has impacted not only music but fashion while becoming mainstream in the process.

Fortunately, I know someone who was there when “streetwear” was first happening on the

street. Someone who watched it emerge from the nascent Hip Hop scene in The Bronx.

Someone who watched it become the mainstream.

It was me.

The Dunks you’re wearing, with or without the collaboration of Off-White? I wore them before you.

As a matter of fact, the Dunks you’re rocking now are essentially the ones I rocked growing up. I rocked Kentucky’s; Royal Blue and White.

As a native New Yorker reared in the ‘80s and ‘90s in Manhattan and The Bronx, I was an

eyewitness, a participant and a consumer of Hip Hop culture. You could say we grew up

together.

An image of a man dressed in 80’s and 90’s Hip Hop fashion.

A tale of two boroughs: My fashion journey in NYC

I was born at Columbia-Presbyterian, raised in the West Village and The Bronx, and educated in Riverdale. Everything about my past serves me sartorially today; my style reflects the prep school values of my upbringing and the Hip Hop sensibility of my environment.

OCBDs in every plaid imaginable? Check.

Lee jeans in various flavors? Check

.

Cotton and wool knit ties? Check.

Sneakers with no laces or untied “fat laces” so thick you couldn’t see the tongue of the sneaker? Check.

I went to school in The Bronx. First at Little Flower Montessori in Riverdale, then Riverdale Country School, then Our Saviour Lutheran.

As I transitioned from RCS to OSL, I went from living with my mother in the Village to living with my Grandparents in the Soundview section of The Bronx. To say it was a culture shock would be like saying basketballs are orange.

Going to school in The Bronx was one thing. Going to live there was an entirely different thing. I would have to get my passport stamped.

The South Bronx in the 1980s.

The Language of Hip Hop: My Universal Connector

In Soundview, I felt like an alien.

At school, I wore an open collar button down with a tie and a sport jacket with khakis and a leather belt and hard leather shoes.

Then I would come home and change into my Hip Hop outfit: a dark navy Adidas t-shirt with 3D letters with a beautiful shade of gray Lee’s, a gray web belt, and gray suede Adidas Campus with gray fat laces that were never tied.

My new neighbors and I spoke the same language but with entirely different dialects. Eventually, I realized there was one language we both shared and were equally fluent: Hip Hop.

Crosstown from my grandparents’ place in Soundview were the Bronx River Houses where the Rock Steady Crew and Afrika Bambaataa and the Mighty Zulu Nation were building the foundation of Hip Hop.

Bambaataa and Zulu once came to our block looking for someone, presumably to beat down (shoutout to Zulu Dave wherever you are).

My Grandparents also lived blocks away from Soundview Park where DJs set up their equipment and MCs rapped.

I had no idea that lampposts had outlets where you could plug in your equipment. These guys were innovative, magical and technical. Who knew?

Soundtrack of My Youth: The Rise of Hip Hop Music

When “Planet Rock” by Afrika Bambaataa and the Soul Sonic Force came out it was a phenomenon. That’s really the only way I can describe it. It came out in the Summer of 1982.

First, someone told you about it and you didn’t know what they were talking about. Then they hummed it for you. You still didn’t know it. Then you heard it on WBLS, 107.5. And you lost your mind. You never heard a song like this.

The way the beat played made you immediately want to move even if for some crazy reason you didn’t want to.

“Rock, rock to the Planet Rock. Don’t stop.”

I played it over and over and over in my house until my Grandparents grew tired of it. And then I played it some more. It helped me learn how to attempt to breakdance and do the “Electric Boogie” which essentially is popping and locking, New York City style.

The record store in my neighborhood played it over and over. And it was delightful.

That song was the soundtrack for Rap and Hip Hop and the main guy, Afrika Bambaataa, lived a stone’s throw away from me.

An image of American DJ and rapper Afrika Bambaataa.

Vinyl adventures: Discovering music in the Bronx

At the shopping center a few blocks away from the house, there was a record store between a dry cleaner’s and an arcade.

You didn’t really go to this record store to buy record albums. You went there to buy 12 inch singles of songs.

Some of them would have the instrumental on the other side, the B side. Some of them would have a shortened, radio version of the song. Some of them would have a remix. Some of them would have an entirely different song on the other side.

When you approached the place, you could hear it as well as see it because there was a big speaker set up in front of the store playing whatever they were playing inside.

You could ask whoever worked there to play a song before you bought it, as long as they had already opened the record you wanted.

Sometimes you would ask them if they had a song and if they asked you the name and you didn’t know it, you would say, “It goes like this” and then you would hum or sing it.

If you were good at that, they would recognize it. “Oh, you mean, “Genius of Love?” We got that. Four dollars.”

An image of Tom Tom Club Genius of Love’s album cover.

Rink rhythms: Fashion and fun at the skating palace

My grandparents’ place was just blocks away from Skating Palace, the local roller skating rink. The range of ages went from little kids to young adults. We were in the middle.

The gear? It varied based on the season but a strong Hip Hop influence if you were the age of influence.

Lee colored jeans with your name belt and a Chams de Baron shirt if you were really trying to impress. Le Tigre polo shirts. Mocknecks: long or short sleeved. Just overall Hip Hop style.

I remember when I bought a Skating Palace t-shirt. It was in red. I wore it in all of my subsequent visits so I could pretend I was a skate guard. I still have it in my archives. It was so much fun.

A dark spot with cool lights that played great music. What type of music?

The music of Black and Brown New York: R&B and Rap. The music to make you groove. Fast when you wanted, slow when you wished that you had someone to skate slow with.

My cousin, who was younger than my best friend Daryl and I, was the rocket.

His plan was to go faster than anyone on the rink, full tilt, and then, when he wanted to take a break, exit into the lockers full speed, bumping into people until they either slowed him down or he crashed into the lockers.

I do not think he ever learned how to properly stop. Daryl was the best of the three of us. He had been skating since he was a little kid. Skating Palace was where I learned to groove while I skated, cautiously go backwards and learned to hockey stop.

Flea Market Finds: The Heart of Hip Hop Fashion

When I had a few dollars in my pocket, I’d walk the mile over to the flea market, were there were booths upon booths of clothing vendors, and it was always quiet.

You could buy a Chams de Baron shirt or a Le Tigre polo, brands that you saw on TV and that you had to have.

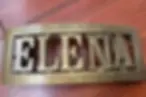

You could buy a “name belt” which was a black or brown leather belt, you picked the color, with a buckle that was either pre made if your name was “Tom” or “Mark.”

If you had a unique name like me (“Reggie”), you went to the guy who had the buckle in the shape of a frame and you spelled or wrote your name and he inserted the letters in the frame and by some act of magic they fit perfectly and never moved.

You could have them in a dirty brownish yellow metal (“Gold”) or dipped into silver or something that looked like silver.

You could also buy a mix tape. The mix tapes were live recordings of MCs performing or battling. This was stuff you couldn’t hear on the radio. It was rap at its rawest.

We would sit outside and listen to it through someone’s “Box.” If there was something we didn’t understand or something we really liked, we’d have the owner of the “Box” hit rewind.

A classic gold buckle with the name ‘Elena.’

Defending The Bronx: My Growing Love for Hip Hop

As Hip Hop grew, my love and defense of The Bronx became stronger and stronger.

By the time I left, I was a passionate, fully indoctrinated, foaming at the mouth defender of The Bronx.

When Boogie Down Productions (BDP) “South Bronx” came on I would yell, glower and move to the beat with an urgency like I was being paid by the borough itself.

Scott La Rock and KRS-One of Boogie Down Productions.

Iconic Streetwear Styles of NYC’s Urban Fashion Scene

A sampling of the stores I went to offering this type of merch, the merch of the streets, were V.I.M., Dr. Jays, Jew Man (from “Fresh Dressed”), Hosiery and stores on 125th Street, Fordham Road, Southern Boulevard and Delancey and Essex Streets.

The consumers and acolytes of this style were young Black and Brown people within the five boroughs with the centerpiece being The Bronx where HipHop was created who were involved in these activities whether actively or passively.

The outfits?

Fitted New Era baseball caps, Kangols: bucket and brimmed, Lee jeans; mostly in color along with denim, name belts, LeTigre polo shirts (a brand undergoing a renaissance), mock necks, Clark Wallabees, Distino “Straps”, Playboys, British Walkers, Cazal and Sergio Valente glasses, leather goose down parkas, shearling coats aka “sheepskins”, and Chams de Baron dress shirts.

I often went back into Manhattan because it was my home turf and what I knew the best.

Haggling and hustle: My escapades at Hosiery and Jew Man

Hosiery and Jew Man were walking distance from my house.

Hosiery was a joy to go to. The store was very vertical so they had to get someone with a “grabber” to snare the jacket or jeans or tops you wanted. It was a fun experience.

Jew Man was another story.

First, at Jew Man, you had to haggle which was only something you did in the Lower East Side in which the merchants of the time were Ashkenazi Jews. That was not a skill I had honed at that time.

As a matter of fact, haggling was like another language in which I was not fluent and it made me dizzy. You also had the determine the risk/reward of purchasing something “Fresh” versus your life.

There were always two lines at Jew Man. One to buy and one to get robbed. I probably planned for at least a year the only trip I made there. I was terrified with all of those stories I heard.

Steve Crawley, who was my friend and my neighbor, convinced me that no harm would come to me if we went. We walked there. As we approached the store, my head and neck miraculously went 360 degrees in the effort to spot the thieves that were going to “vic” us.

We went in, they talked very fast, I stumbled and I asked for a pair of Calvin Klein jeans. I remember it being hot, crowded and stuffy. They didn’t have the color I wanted and they offered me a pair in turquoise.

I knew no one had that. I took it and lamely asked for five dollars off the asking. I got it. I walked out in full walk/race mode like I was in the Olympics with Steven smiling because I didn’t get stuck up while in the store.

The transaction lasted less than five minutes. I made it home with my life and my jeans. I wore them for years. They looked really good with espadrilles.

NYC’s VIM Jeans and Sneakers store.

Supreme: From Skate Culture to Fashion Giant

Supreme (which recently was bought by VF Brands) is a great example of a ‘90s New York City skateboard brand

Supreme embraced HipHop, especially the backpack rap posse who also skateboarded, married them and gave the legitimacy of the street to kids (and later adults as time went on)

who could and could not afford the decks and their gear which would include Nike SB, a Dunk line adapted for their community.

Like rap, it started as an underground entity and now has become mainstream along with being worldwide. They are now in Italy, Paris, London, Berlin and Tokyo where they have three locations.

I remember the store on Lafayette Street having decks and t-shirts with no merchandise in the center of the floor to seeing a line down the block to seeing a bouncer and a velvet rope. (Long live Lafayette Street).

They do two collections a year with limited runs. Their drops online have helped create another industry: Shopping bots.

They entered the luxury market with one of the fashion industries most successful collabos ever with Louis Vuitton.

James Jebbia, the creator of the brand, won the 2018 Menswear Designer of the Year by the CFDA: Council of Fashion Designers. A classic flyer promoting Roller Concert 1’s live concert at Skatin Palace. A classic flyer promoting Roller Concert 1’s live concert at Skatin Palace.

An image of Supreme’s brand logo.

The Evolution of Sneaker Culture in the Hip Hop Era

Sneaker brands and stores during the 1980s were transforming from merely outfitting kids who played sports or who wore them every day as a casual alternative to wearing shoes to being the foundation of the Hip Hop outfit.

During that time Sports Illustrated and Nike, along with Converse, Pony and a bunch of smaller brands (Diadora, Etonic, New Balance, Avia, etc) were selling and displaying posters of NBA players: In motion or staged.

This was an opportunity to see certain sneakers up close and if the poster was in the store, you would know exactly what you wanted to buy.

“Let me get the Georgetowns.” “Do you have the Ewings?”

Names like Nike, Adidas, Puma, Converse, Pony, Saucony, New Balance, Fila, Diadora, Lotto and Troop were the ones that seized the attention of the HipHop nation.

Low tops, mid tops and high tops were the options in bright colors and strong graphics. Of all the brands listed, some names were bigger than the rest: Nike and Adidas.

My Nike Moment.

I remember going to a shoe store on Simpson Street and Westchester Avenue (it’s a CVS now).

It was around the corner from the famous 41st Precinct also known as “Fort Apache” and seeing the famous Nike poster of George Gervin aka “The Iceman” of the San Antonio Spurs sitting on a bed of ice palming two basketballs with a gray track suit that had the name “Ice” on the left breast.

I had to get a Nike suit like that, and I did and I rocked it hard with the pants legged stuffed into thick gray socks which of course were inside a pair of white and light blue Nikes accessorized with a thin gold herringbone chain that my Grandparents got me as a gift with an eighth note pendant my High School sweetheart Tuvana got me.

I was fly as hell.

An image of Nike’s vintage Iceman poster.

Nike and Adidas: The Titans of Hip Hop Fashion

Both Nike and Adidas were the kings of Hip Hop fashion. Let’s break it down.

Nike's pioneering styles

Nike, between the relaunch of the Cortez in 1980, the launch of Air Force Ones in 1982 and Dunks and Air Jordan’s in 1985, rode on the wave that Hip Hop created and capitalized on it.

They were instrumental in providing sneakers and athletic gear, even if you weren’t an athlete, that met and stoked the demand for “sneaker culture” that still exists today.

The Cortez, in leather and in nylon, was a Hip Hop sneaker and the choice of breakers and electric boogie dancers.

I was fortunate enough to have convinced my Grandparents to buy me a white leather pair with the red stripe with the blue and white striped cushioning. After every wearing, I would clean and scrub them with a toothbrush, a sponge and some Comet.

Eventually, I used Kiwi white liquid polish to aid me in the upkeep. I was in love with them. The colorway was so clean and classic.

A few years ago, I saw a friend of mine with a pair. I couldn’t believe it. It took me back in time. So much so, I copped a new pair. The same colorway. I’ve never done that before or since.

They are still fresh decades later. I love them.

AF1s initially were a New York City sensation, so much so that they were called “Uptown’s” in homage to Harlem.

Dunks started out as a sneaker for NCAA men’s basketball with St. Johns in Queens, where Run-DMC went to school, as one of the eight charter programs to initially wear them, the others being Iowa, Kentucky, Michigan, Georgetown, UNLV, Arizona and Syracuse.

The line eventually did a spinoff in skateboarding (SBs) and in 1999, the WuTang Dunks came in only 36 pairs based on “Enter the WuTang: 36 Chambers.” That was a “limited drop”, a term often used today.

The rebel shoes that redefined the NBA and sneaker culture

When Nike launched Air Jordan’s in 1985 it almost immediately became a “rebel” shoe, much like the rap music that was being listened to at that time.

The initial colorway of red and black or “Black with the red stripes” as we called it, was banned by the NBA. They were banned by then Commissioner David Stern (RIP) for having very little white in them, which was one of the colors of the Bulls uniform.

It was known then as the “51 percent” rule. 51 percent of the shoe had to be white and in accordance with what the rest of the team was wearing.

You must wear shoes that not only matched your uniform but matched the shoes of your teammates (it has since been repealed which is why you know see players rocking flavors that don’t come close to matching the uniform).

As a result of this, Nike began to advertise the sneaker as “The one that was banned by the NBA.” That, along with Michael Jordan being such an incredibly exciting and athletic player, led them to be the best selling shoe of the year.

The cool colors of the Chicago Bulls probably helped as well: Red, black and white.

Lines formed around the block at certain stores. A new version has come out every year. Re-releases are dropped every few years. This is the “capsule collection” that you hear about now.

An NBA letter to Nike banning Michael Jordan’s red and black shoes.

Run DMC’s Million-Dollar Endorsement

Run DMCs endorsement deal with Adidas in 1986 for one million dollars reinforced the ascendancy of rap as a legitimate art form with crossover abilities.

The deal was consummated soon after Adidas exec Angelo Anastasio saw thousands of concertgoers at Madison Square Garden take off their kicks after Run of Run-DMC told them to take their Adidas off and put them in the air as a prelude to them performing their song, “My Adidas.”

My best friend Daryl attended that concert. People were also robbed for their Adidas that day.

Their song “My Adidas,” which is an ode to the Adidas Superstar aka “Shellheads” that they wore untied with no laces, is one of the best unpaid advertising campaigns ever for a consumer brand and probably greased the rails for the deal to happen.

The “Raising Hell” album, which came out the same year with that song and with their version of “Walk This Way” with Aerosmith later went triple platinum.

Triple platinum status was proof that Hip Hop, through Rap, was growing beyond the five boroughs. Beyond other urban centers. It was spreading to the suburbs. And the Heartland. And the world.

It led to old school comic Rodney Dangerfield come out with a rap song as “Rapping Rodney.” “The Flintstone’s” Barney Rubble rapped to get a bowl of Fred’s “Fruity Pebbles” cereal in a commercial.

If you love “The Transformers,” Blaster had a cadence that rhymed (check out his flow). If you love dolls there was “Rappin’ Rockin’ Barbie” with a boombox. Movies like “Beat Street,” Krush Groove” and “Breakin’” reflected the growth of the culture with successful box office openings.

The crossover was happening.

By the way, I bought the Run-DMC Adidas sweatshirt from the shoestore on Simpson Street and Westchester Avenue.

The audience raising their Adidas Superstar sneakers during a Run DMC concert.

Sneaker Brands Branch Out

Sneaker brands also came with apparel which led the youth to accessorize.

Of all the choices offered at the time, the tracksuit, which was also broken down into corresponding separates; track jackets and track pants, provided a look that added a level of coolness for the Hip Hop kids and one of casualness to everyone else.

The wearing of this outfit became acceptable for non-sports activities (though breaking is a very athletic physical dance form and DJing is also significantly physical). It wasn’t just for athletes anymore.

The tracksuit also became the attire of Italian Americans living in New York City. The elastic waistband with the drawstring helped anyone with a wide girth. Tracksuits have made a strong comeback (or maybe they never left?).

The Juicy Couture renaissance? We’re talking to you velour. Suits with drawstrings? You can thank trackpants and sweatpants.

An image of American rapper LL Cool J.

The Renaissance of 80s and 90s Fashion

The ‘80s and ‘90s are hot now which is a testament to their influence. Some brands of that era are now being revisited and revitalized.

How do I know all this?

I was there. I’ve even bought into the renaissance.

Le Coq Sportif, Sergio Tacchinni, Kappa and Fila are in my closet. The first three brands I didn’t have as a kid, the fourth is a revisiting.

I’ve given away my navy hightop Formula 1 Diadoras which are too tight all of a sudden. The Yankees Starter jacket with the Spring lining I had back then is now the Yankees Mitchell and Ness jacket with the Spring lining.

The Nike and Adidas track suits I also had back then are the Fila, Adidas, Puma, Nike, Sergio Tacchinni and Kappa track jackets and Kappa and Fila track pants I have now. Strictly separates.

An image of iconic streetwear brand logos in the 80s including Sergio Tacchini, Fila, and Puma.

This is all the streetwear that was adopted from back then and continued on to this present day. The fact that I’m wearing some of these things now is a testament to that.

I, willingly, am the sartorial bridge between the old and the new school. And don’t get me started on logos (perhaps another article?).

The current streetwear and athleisure scene could not be nearly as prevalent or as successful as it currently is without the foundational influence of Hip Hop.

I’m a classic menswear guy, no longer a sneakerhead. But there are a few styles I will always love.

Dunks: A Summer to Remember

So remember when I said I wore the first generation of Dunks?

The Summer of 1985 was one of my best Summers ever. Why?

It was the Summer that I bought a pair of Dunks. They were royal blue and white. The Kentucky colors. The Wildcats. The team of Kenny “Sky” Walker who was drafted by the Knicks and won the NBA Slam Dunk Contest in 1989.

I looked at them for weeks. For months.

For the Summer, I was a camp counselor at my church’s vocation bible school, third generation after my mom and my grandparents. My Summer, my rules so I saved up my money to get them.

I don’t remember how much they cost but they were definitely under $100.

The biggest coup I pulled off was convincing my best friend Daryl Walker to buy the very same Dunks. And he agreed!

Friendship, music, and matching sneakers

It would be our Summer. We would be brothers. I was so excited.

My Grandparents loved Daryl and treated him like another grandson which was fine for me because he was my best friend. I wanted to do everything with him.

We loved music and we listened together and hipped each other to the songs and artists that sometimes the other didn’t know. We loved model trains and we collected them, O27 gauge for me and HO for him.

Getting the same sneakers was like us becoming blood brothers. That was a glorious Summer for me.

People would see us together and if we both happened to be wearing the same sneakers they would comment and I would be on a cloud. They noticed! We would stick out our feet like we were sneaker models so whoever commented could see us side by side.

The neighborhood noticed too. They teased us. I couldn’t care less. They weren’t my best friend. They weren’t my Brother. Daryl was.

Unfortunately, Daryl couldn’t take the observations, the compliments and the teasing. He started to hate that he ever bought those Dunks.

It didn’t stop our friendship but we never did anything like that again. For me it was the best Summer ever. For him? I’m sure he would have liked a do over.

Dunks have made a comeback and an expensive one at that.

Thanks Virgil Abloh (Rest In Peace). Jordan’s never left and I still refuse to wear them. I’m a Knicks fan.

The Nike Dunk Low in the Kentucky royal blue and white colorway.

If you need help coordinating your streetwear, feel free to reach out to me.